Test-Time Inverse Scaling in Audio LLMs

Published:

Chain-of-thought prompting has transformed text-based LLMs. Models like OpenAI o1 and DeepSeek-R1 show that explicit reasoning dramatically improves performance. But something counterintuitive happens in Audio LLMs: more reasoning makes things worse. This post explains why, what’s actually going wrong inside the reasoning chains, and how process-level rewards resolve the issue.

Table of Contents

- The Scaling Paradox

- Why Reasoning Goes Wrong

- Process Rewards: Supervising How the Model Thinks

- The Reasoning Sweet Spot

- Beyond Reasoning: Synergistic Effects

- Broader Lessons

- Summary

- References

The Scaling Paradox

In text LLMs, there’s a reliable pattern: allocating more compute to reasoning at inference time (longer chain-of-thought, more tokens to “think”) tends to improve performance. This is the foundation of test-time scaling — the principle behind reasoning models like o1, R1, and QwQ.

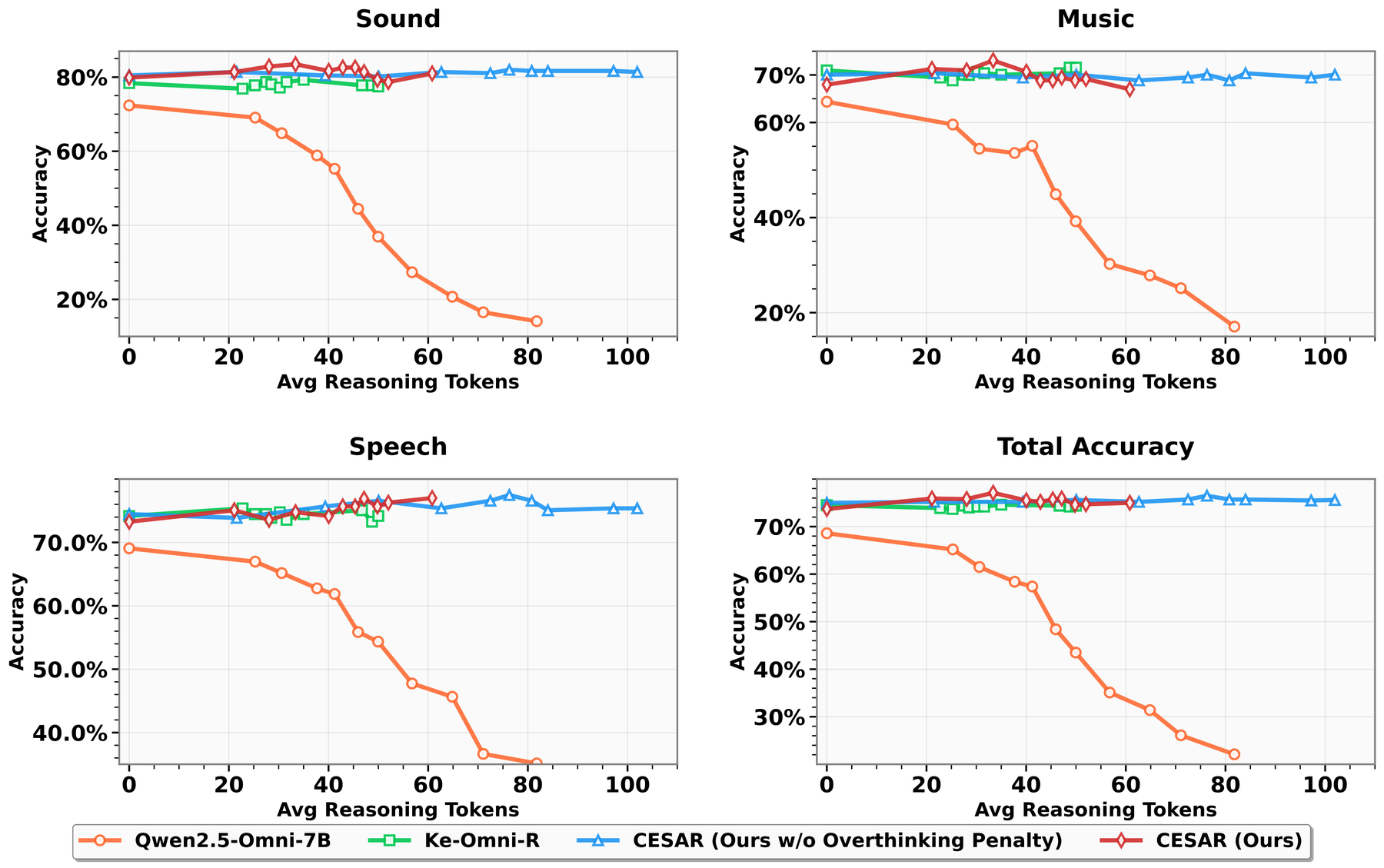

Audio LLMs tell a different story. When you allow an Audio LLM to reason before answering, performance often degrades. When you let it reason longer, it gets even worse:

\[\frac{\partial P(L_{\text{max}})}{\partial L_{\text{max}}} < 0\]where \(P(L_{\text{max}})\) is accuracy when the model is allowed up to \(L_{\text{max}}\) reasoning tokens.

We call this test-time inverse scaling: the more the model “thinks,” the worse it performs.

This isn’t subtle. Models that achieve 70%+ accuracy with direct answers can drop to below 60% when forced to reason. The reasoning itself is actively harmful.

The natural conclusion might be: “reasoning just doesn’t work for audio.” But that’s wrong. The problem isn’t reasoning itself — it’s how models are trained to reason.

Why Reasoning Goes Wrong

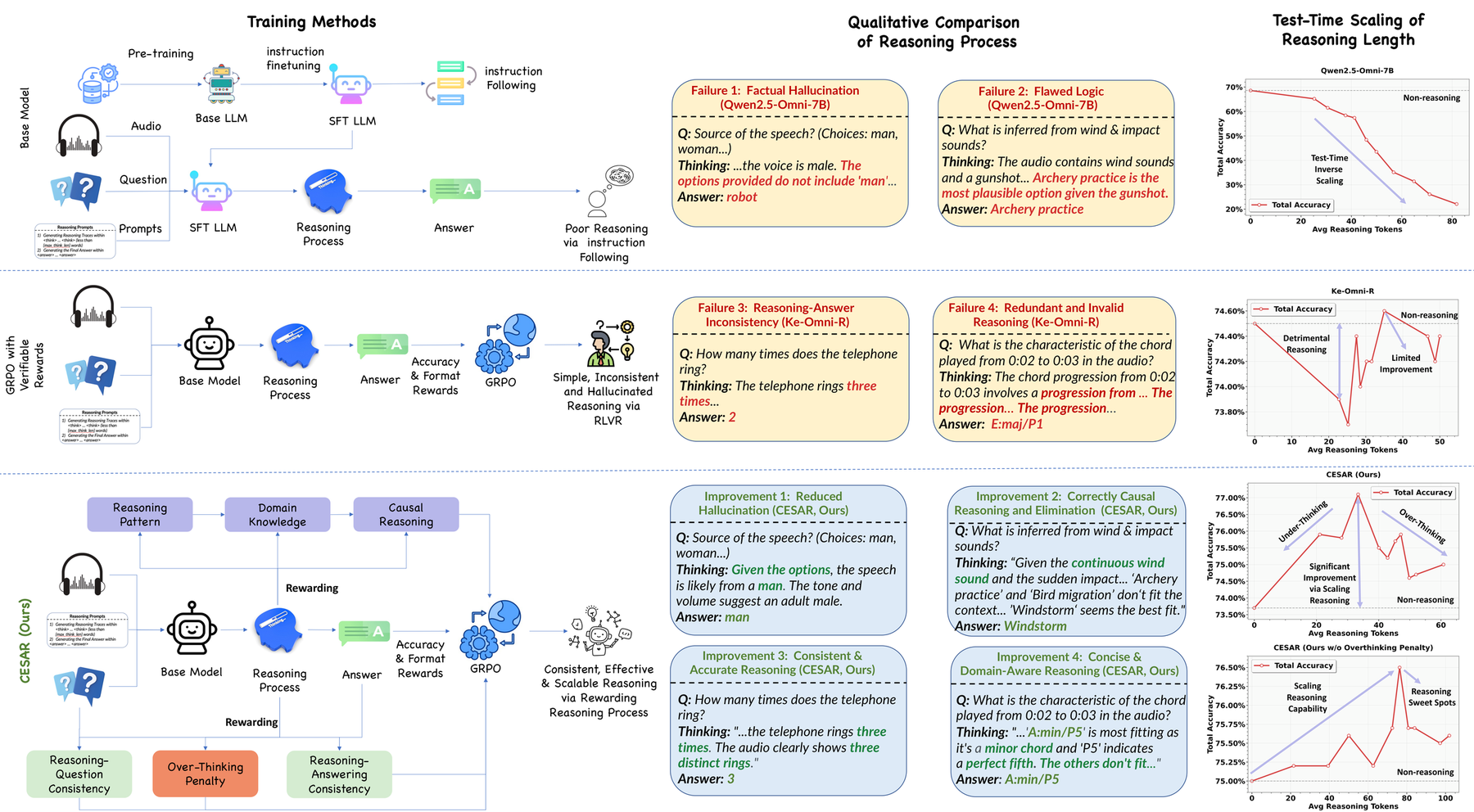

The training gap

Current RL approaches for Audio LLMs use outcome-only rewards:

\[R_{\text{RLVR}}(s_i) = \mathbb{I}[\hat{y}_i = y_i] + \mathbb{I}[\text{ValidFormat}(s_i)]\]The reward checks two things: “Is the final answer correct?” and “Is the output properly formatted?” That’s all. The entire reasoning chain \(t_i\) — which could be hundreds of tokens — is completely invisible to the reward function.

This means the model gets the same reward whether its reasoning is:

"The audio contains a clear piano melody in the major key, with a tempo around

120 BPM. The harmonic structure suggests classical rather than jazz..." → Answer: B

or:

"Let me think about this. I think the answer might be something. Actually let me

reconsider. The sound is interesting. Maybe it could be several things..." → Answer: B

As long as the final answer is correct, both receive identical reward. The model has zero gradient signal to improve reasoning quality.

Three failure modes

Without supervision of the reasoning process, three specific pathologies emerge:

1. Hallucinatory reasoning. The model generates plausible-sounding but factually wrong analysis — describing instruments that aren’t present, inventing acoustic properties, confabulating music theory. Each additional reasoning token is another opportunity to introduce a hallucination, and hallucinations compound across the chain.

2. Reasoning-answer inconsistency. The reasoning says one thing, but the answer says another. Example:

“The audio clearly contains a piano solo… therefore the answer is drums.”

With outcome-only rewards, the model can learn to produce correct answers despite wrong reasoning. The reasoning becomes decorative noise disconnected from the answer. Longer chains amplify this noise.

3. Unstructured, circular reasoning. Without guidance on how to reason, models develop rambling patterns: repeating observations, circular logic, tangential elaboration. No systematic analysis structure (elimination, comparison, deduction) emerges.

Why doesn’t reasoning emerge naturally?

In text LLMs, reasoning does emerge somewhat naturally from outcome-only training (though process rewards still help). Why is audio different?

The key difference is the modality gap. Text reasoning can leverage massive amounts of pre-training data that already contains reasoning patterns (textbooks, proofs, tutorials). The model has seen millions of examples of structured argumentation.

Audio reasoning has no such foundation. Pre-training on audio-text pairs teaches the model to describe audio, not to reason about it. When you then ask it to reason via RL, it has no templates to draw from — so it generates text that looks like reasoning but isn’t grounded in actual audio analysis.

Process Rewards: Supervising How the Model Thinks

The fix is to reward not just the final answer, but the reasoning process itself. CESAR introduces a multi-faceted reward suite:

\[R_{\text{total}}(s_i) = \underbrace{\alpha_1 R_{\text{acc}} + \alpha_2 R_{\text{format}}}_{\text{outcome (existing)}} + \underbrace{\alpha_3 R_{\text{consistency}} + \alpha_4 R_{\text{keywords}} + \alpha_5 R_{\text{overthinking}}}_{\text{process (new)}}\]Each process reward targets a specific failure mode:

Reasoning consistency reward

\[R_{\text{consistency}}(s_i) = \text{Sim}(t_i, \hat{y}_i) + \text{Sim}(t_i, Q_i)\]This measures semantic alignment in two directions:

Reasoning ↔ Answer (\(\text{Sim}(t_i, \hat{y}_i)\)): Does the reasoning logically lead to the chosen answer? This directly combats reasoning-answer inconsistency.

Reasoning ↔ Question (\(\text{Sim}(t_i, Q_i)\)): Is the reasoning actually about the question asked? This prevents hallucination — the model can’t ramble about unrelated topics.

Similarity is computed via concept overlap:

\[\text{Sim}(x, y) = \frac{|\text{Concepts}(x) \cap \text{Concepts}(y)|}{\max(|\text{Concepts}(x)|, |\text{Concepts}(y)|)}\]This is deliberately simple — no learned model, no LLM judge, just lexical overlap of key concepts. The simplicity is a feature: it provides a stable, deterministic gradient signal without introducing the complexity and variance of learned reward models.

Structured reasoning keywords

\[R_{\text{keywords}} = R_{\text{pattern}} + R_{\text{logic}} + R_{\text{domain}}\]Three components that serve as cognitive scaffolding:

Analytical patterns (\(R_{\text{pattern}}\)): Detects and rewards structured reasoning strategies — elimination (“Option A is unlikely because…”), comparison (“Comparing the tempo to…”), step-by-step analysis (“First, I’ll analyze the frequency spectrum…”). These patterns don’t emerge reliably from outcome-only training.

Logical connectives (\(R_{\text{logic}}\)): Rewards markers of genuine logical reasoning — causal chains (“therefore,” “because”), hypotheticals (“if the tempo were…”), evidence-based conclusions (“based on the harmonic content…”). Promotes coherent logical progression rather than stream-of-consciousness.

Domain vocabulary (\(R_{\text{domain}}\)): Rewards audio-specific terminology — acoustic properties (timbre, frequency, amplitude), musical concepts (tempo, key, chord progression), speech features (prosody, formants). This grounds reasoning in the actual audio signal rather than generic text patterns.

Overthinking penalty

\[R_{\text{overthinking}}(s_i) = 1 - \frac{|t_i|}{L_{\text{max}}}\]A linear penalty on reasoning length. This is the essential counterpart to keyword rewards — without it, the model could game the keyword reward by producing verbose, repetitive reasoning stuffed with trigger words.

The penalty forces the model to be concise. Combined with the keyword reward, the optimization pressure becomes: “reason in a structured, domain-grounded, logically coherent way — and do it efficiently.”

The Reasoning Sweet Spot

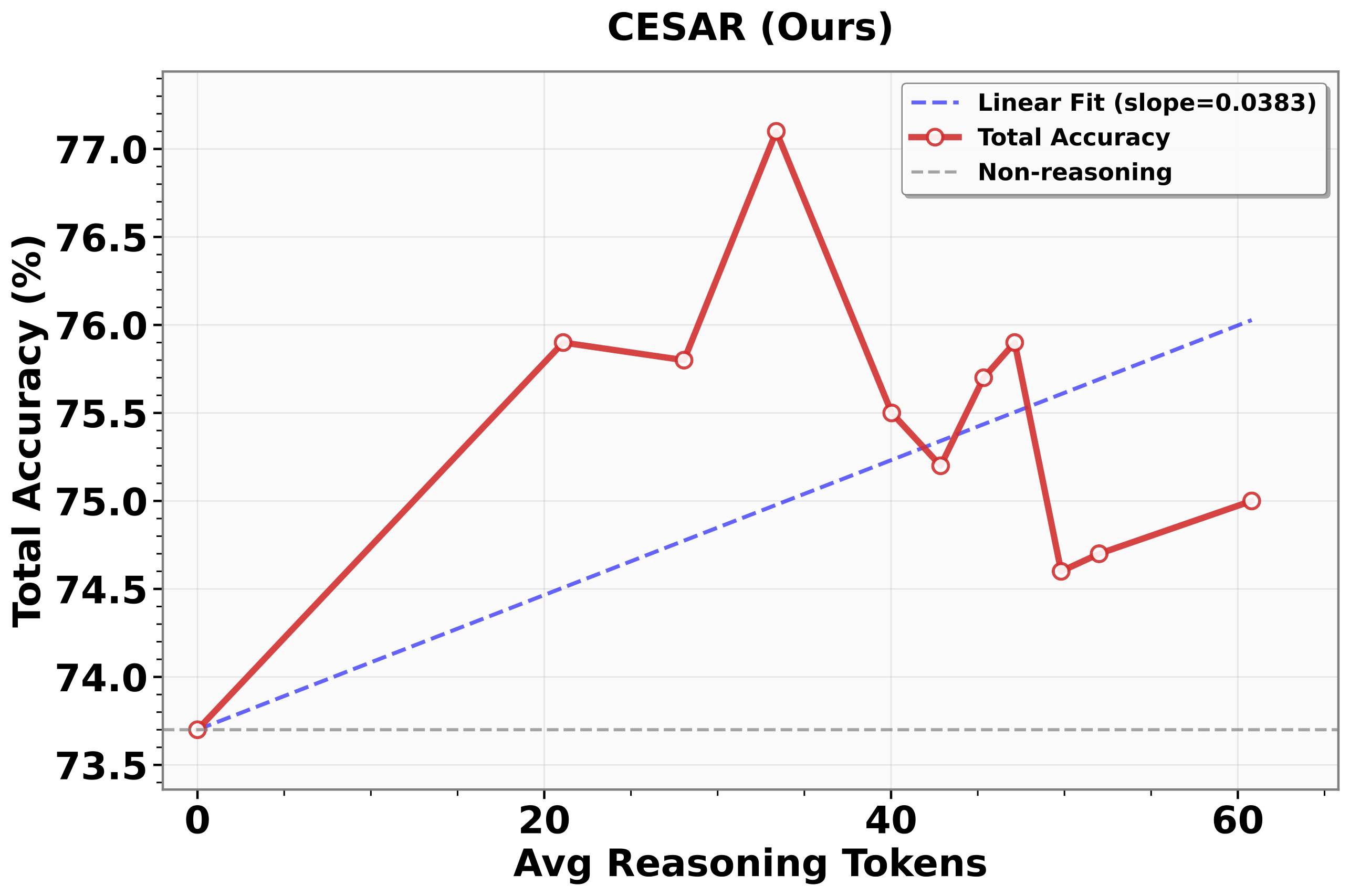

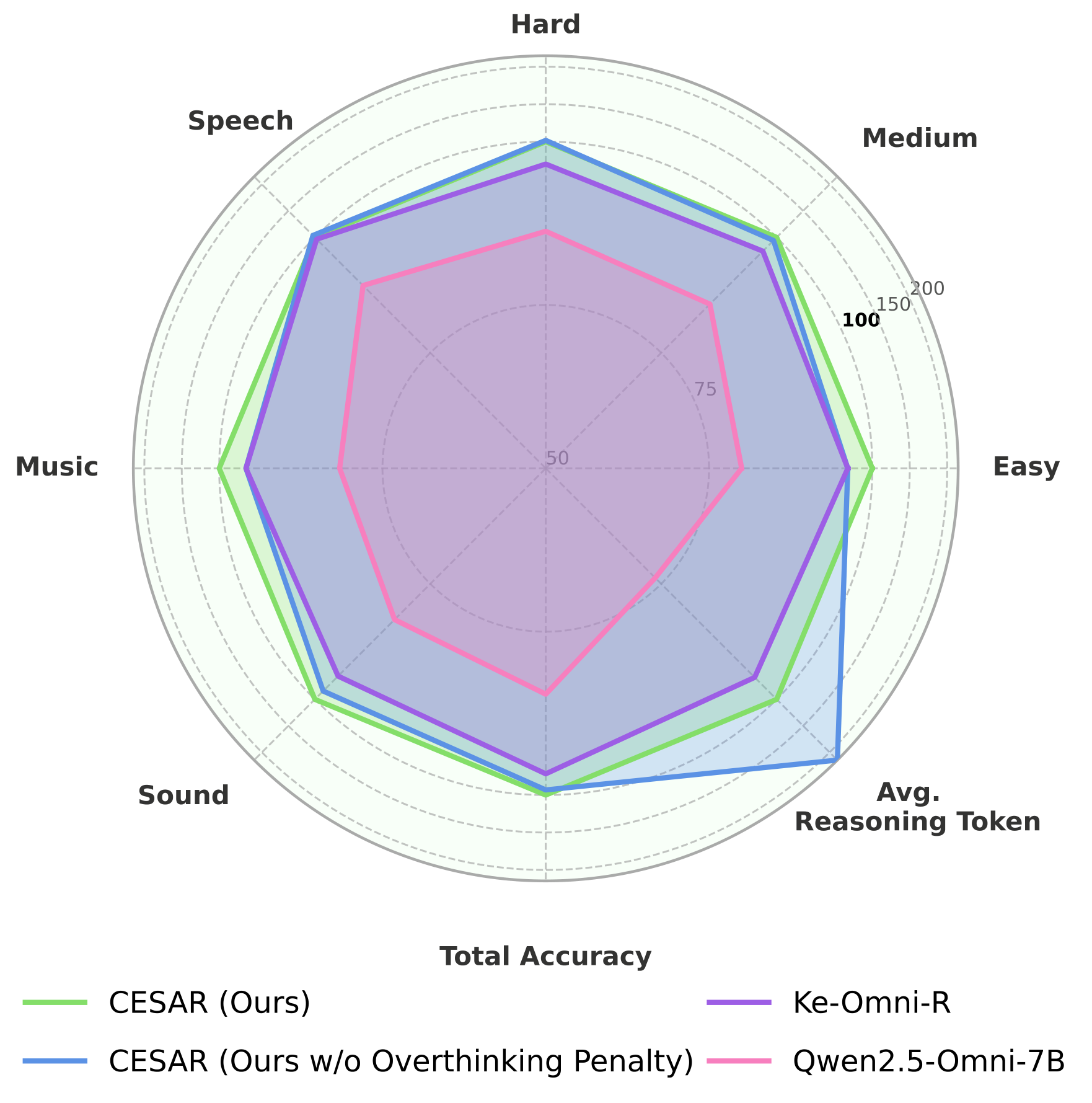

With process rewards, test-time inverse scaling reverses. Performance now increases with reasoning length, up to a model-specific optimum:

\[L_{\text{sweet}} = \arg\max_L P(L)\]CESAR discovers “reasoning sweet spots” where the model achieves peak performance. Below this point, the model lacks sufficient analytical depth. Beyond it, returns diminish (but don’t degrade — a critical difference from baselines).

The scaling slope — whether performance increases or decreases with more reasoning — is perhaps the most important metric. A positive slope means the model has genuinely learned to reason. A negative slope means it’s just generating noise that happens to sometimes contain correct answers.

Beyond Reasoning: Synergistic Effects

An unexpected finding: improving reasoning quality also improves perception capabilities. Models trained with process rewards become better at basic audio understanding tasks (identifying instruments, recognizing speakers, detecting events) — even though these tasks don’t require explicit reasoning.

This suggests that reasoning and perception are deeply entangled in multimodal models. Learning to reason about audio signals forces the model to develop better internal representations of those signals. The process rewards act as an implicit regularizer that shapes how the model attends to and processes audio features.

Broader Lessons

1. Process supervision matters

The parallel to education is direct. If you only grade students on final exam answers, some will learn the material and some will learn to guess well. If you also evaluate their work (proofs, derivations, reasoning steps), you select for genuine understanding. Outcome-only rewards are like grading only final answers.

2. More compute is not automatically better

Test-time inverse scaling is a cautionary tale for the “just scale it” mentality. Without proper training, additional inference-time compute is wasted or harmful. The bottleneck is not compute — it’s the quality of what the model does with that compute.

3. Simple rewards can be powerful

CESAR’s process rewards are deliberately simple — concept overlap, keyword detection, length penalty. No learned reward models, no LLM judges, no complex architectures. The power comes from providing any gradient signal on reasoning quality, where previously there was none. Going from zero supervision to basic supervision of the reasoning process is the critical step.

Summary

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hallucinatory reasoning | No feedback on reasoning content | Consistency reward (reasoning ↔ question) |

| Reasoning-answer disconnect | Reward ignores reasoning chain | Consistency reward (reasoning ↔ answer) |

| Unstructured thinking | No template for audio reasoning | Keyword rewards (pattern + logic + domain) |

| Verbose rambling | No length pressure | Overthinking penalty |

| Test-time inverse scaling | All of the above compounding | Multi-faceted process rewards |

The key insight: test-time inverse scaling is a training problem, not a fundamental limitation of reasoning in audio. Process rewards resolve it by providing the gradient signal that outcome-only rewards lack.

References

[1] Fan et al. “Incentivizing Consistent, Effective and Scalable Reasoning Capability in Audio LLMs via Reasoning Process Rewards.” ICLR 2026. Paper

[2] Shao et al. “DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models.” 2024. (GRPO)

[3] Wei et al. “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models.” NeurIPS 2022.

[4] OpenAI. “Learning to Reason with LLMs.” 2024. (o1)

[5] DeepSeek-AI. “DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning.” 2025.

Cited as:

Fan, Jiajun. "Test-Time Inverse Scaling in Audio LLMs."

jiajunfan.com (2025).