The Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma in RLHF for Generative Models

Published:

RLHF fine-tuning of generative models faces a fundamental tension: you want to maximize reward (make outputs better), but doing so aggressively destroys the diversity of what the model can produce. This post explains why this happens, why it’s hard to fix with a single hyperparameter, and how advantage-based adaptive regularization provides a principled solution.

Table of Contents

- Background: The RLHF Objective

- The Diversity Collapse Problem

- The Fixed-β Dilemma

- Adaptive Divergence Regularized Policy Optimization (ADRPO)

- What Emerges in Practice

- Summary

- References

Background: The RLHF Objective

Suppose you have a pre-trained generative model \(\pi_{\text{ref}}\) — a text-to-image model like Stable Diffusion 3, or a language model like Qwen. You want to fine-tune it so that its outputs score higher on some reward function \(R(x, c)\), where \(x\) is the generated output and \(c\) is the conditioning context (e.g., a text prompt).

The standard approach formulates this as a regularized optimization problem:

\[J(\theta) = \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{x \sim \pi_\theta, c \sim p(c)}[R(x, c)]}_{\text{maximize reward}} - \underbrace{\beta \cdot D(\pi_\theta, \pi_{\text{ref}})}_{\text{stay close to pre-trained model}}\]The first term says “produce high-reward outputs.” The second term says “don’t stray too far from the original model.” The coefficient \(\beta\) controls this trade-off, and \(D\) is some divergence measure — KL divergence for language models, Wasserstein-2 (W2) distance for flow matching models.

This is clean and intuitive. But in practice, getting \(\beta\) right is surprisingly hard — and the consequences of getting it wrong are severe.

The Diversity Collapse Problem

What happens without regularization

Let’s start with the extreme case: \(\beta = 0\), no regularization at all. The model is free to do whatever maximizes reward.

In online RL, the model generates samples, gets rewards, and updates itself. Without any constraint:

- Early in training, the model discovers a few high-reward outputs

- It shifts probability mass toward those outputs

- Now it generates similar outputs more often → they get reinforced further

- This positive feedback loop concentrates all probability mass on a narrow region

The equilibrium is a delta distribution: the model always generates the same output for a given prompt, regardless of the diversity of valid responses.

\[\pi^*_{\beta=0}(x|c) \to \delta(x - x^*_c), \quad \text{where } x^*_c = \arg\max_x R(x, c)\]In image generation, this means every prompt produces essentially the same “optimal” image — perhaps technically high-scoring but boring and unusable. In language, the model repeats the same phrasing over and over.

This is mode collapse (or diversity collapse), and it’s the central failure mode of unconstrained RLHF.

Why diversity matters

One might ask: if the goal is to maximize reward, who cares about diversity? Several reasons:

Reward functions are imperfect proxies. They approximate human preferences, not capture them fully. A collapsed model that exploits quirks in the reward function (reward hacking) produces outputs that score high but look terrible to humans.

Generalization. A diverse model handles novel prompts gracefully. A collapsed model performs well only on prompts similar to its training distribution.

Downstream utility. In creative applications (art, writing, brainstorming), diversity is itself valuable. A model that always gives the same answer is useless for creative tasks.

Training stability. Once the model concentrates on a narrow manifold, gradient signals become noisy and training destabilizes.

The standard fix: fixed regularization

The conventional solution is to set \(\beta > 0\). For flow matching models, we typically use a W2 regularization term:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{ORW-CFM-W2}} = \underbrace{\mathcal{L}_{\text{ORW}}(\theta)}_{\text{reward-weighted flow matching}} + \beta \cdot \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{c,t,x_t}\left[\|\mathbf{v}_\theta(x_t, t, c) - \mathbf{v}_{\text{ref}}(x_t, t, c)\|^2\right]}_{\text{W2 regularization}}\]For language models with GRPO:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{GRPO}} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{PG}}(\theta) + \beta \cdot D_{\text{KL}}(\pi_\theta \| \pi_{\text{ref}})\]This works — to a point. But it creates a fundamental dilemma.

The Fixed-β Dilemma

Here’s the core problem: different samples need different levels of regularization.

Consider two samples generated during training for the same prompt:

| Sample A (high reward) | Sample B (low reward) | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantage | \(A > 0\) (better than average) | \(A < 0\) (worse than average) |

| What we want | Exploit: push further in this direction | Explore cautiously: pull back toward reference |

| Ideal \(\beta\) | Low (give freedom to optimize) | High (enforce stability) |

| What fixed \(\beta\) does | Same constraint as bad sample | Same constraint as good sample |

Fixed \(\beta\) applies the same regularization pressure to every sample regardless of quality. If \(\beta\) is high enough to prevent collapse on bad samples, it also unnecessarily constrains good samples. If \(\beta\) is low enough to exploit good samples, it fails to stabilize bad samples.

This is not a tuning problem — no single value of \(\beta\) is optimal for all samples simultaneously.

Adaptive Divergence Regularized Policy Optimization (ADRPO)

Core idea

The insight is simple: make regularization strength a function of sample quality. High-quality samples get less regularization (exploit); low-quality samples get more (explore safely).

The general ADRPO objective:

\[\boxed{\mathcal{L}_{\text{ADRPO}}(\theta) = \mathcal{L}_{\text{RL}}(\theta) + (\beta_0 - A) \cdot \mathcal{L}_D(\theta)}\]where \(A\) is the advantage estimate for the current sample, \(\beta_0\) is a baseline coefficient, and \(\mathcal{L}_D\) is the divergence regularization loss.

The effective regularization coefficient becomes:

\[\beta_{\text{eff}} = \beta_0 - A\]| Sample quality | Advantage \(A\) | Effective \(\beta\) | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| High reward | \(A > 0\) | \(\beta_0 - A\) ↓ | Less regularization → exploit |

| Average | \(A \approx 0\) | \(\approx \beta_0\) | Standard regularization |

| Low reward | \(A < 0\) | \(\beta_0 - A\) ↑ | More regularization → stabilize |

This is a one-line modification to existing RLHF objectives. No new networks, no complex architecture changes.

For flow matching models

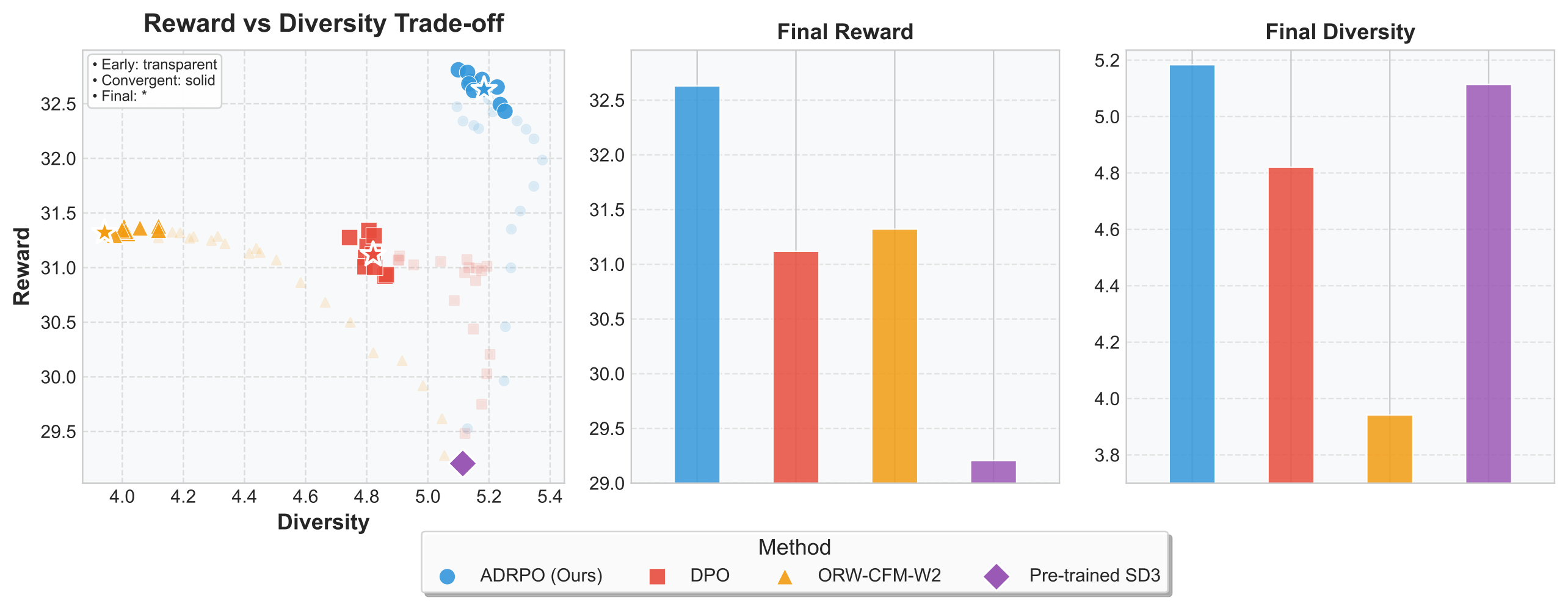

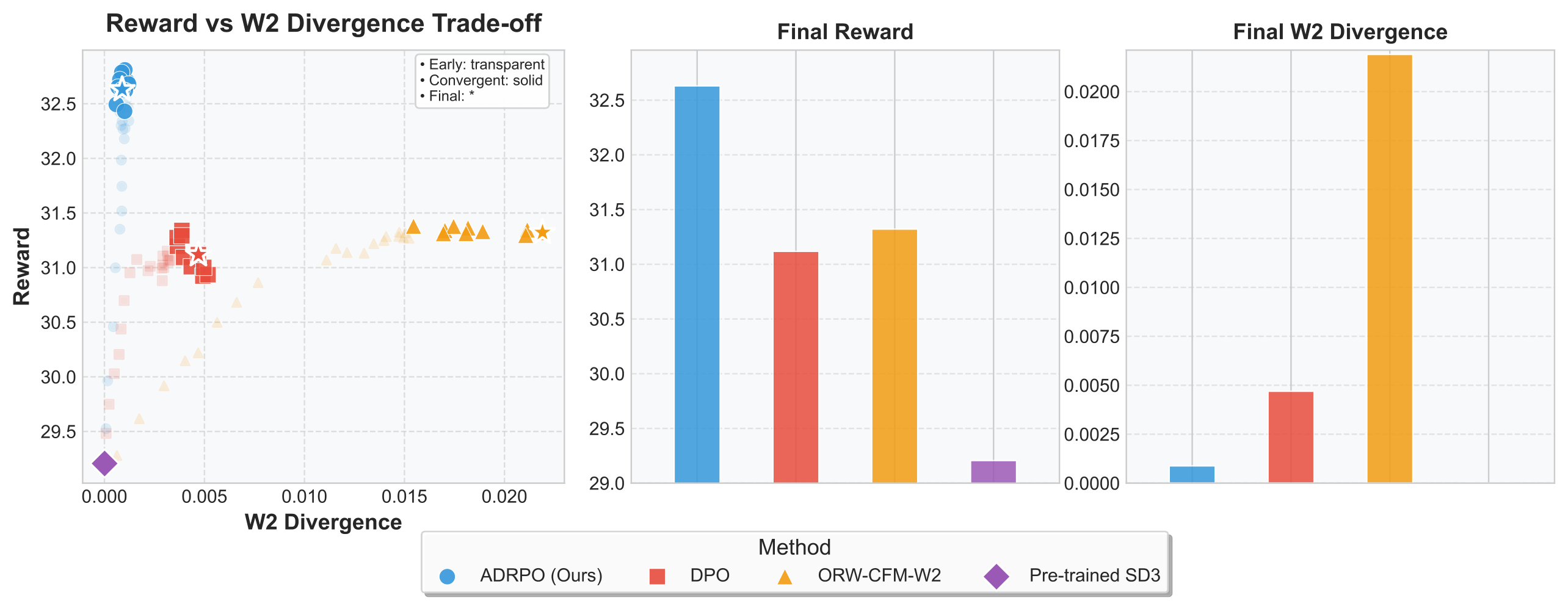

For flow matching models like SD3, ADRPO combines advantage-weighted flow matching with adaptive W2 regularization:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{ADRPO-FM}}(\theta) = \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\left[A(x_1,c) \cdot \|\mathbf{v}_\theta(x_t, t, c) - \mathbf{u}_t\|^2\right]}_{\text{advantage-weighted flow matching}} + \underbrace{(\beta_0 - A(x_1,c)) \cdot \mathbb{E}\left[\|\mathbf{v}_\theta - \mathbf{v}_{\text{ref}}\|^2\right]}_{\text{adaptive W2 regularization}}\]Notice that \(A\) appears in both terms. In the first term, the advantage provides bidirectional learning signals:

- \(A > 0\): gradient encourages matching the target velocity (strengthen good generation)

- \(A < 0\): gradient reverses, actively pushing the model away from bad generation

This is fundamentally different from reward-weighting (ORW-CFM-W2), which can only down-weight bad samples with non-negative weights but never actively suppress them. In high-dimensional spaces like image generation, where bad regions vastly outnumber good ones, this difference is critical.

The advantage is estimated simply as:

\[A(x_1, c) = R(x_1, c) - V(c), \quad \text{where } V(c) = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{B}|}\sum_{x \in \mathcal{B}} R(x, c)\]i.e., the reward minus the batch-average reward for the same prompt.

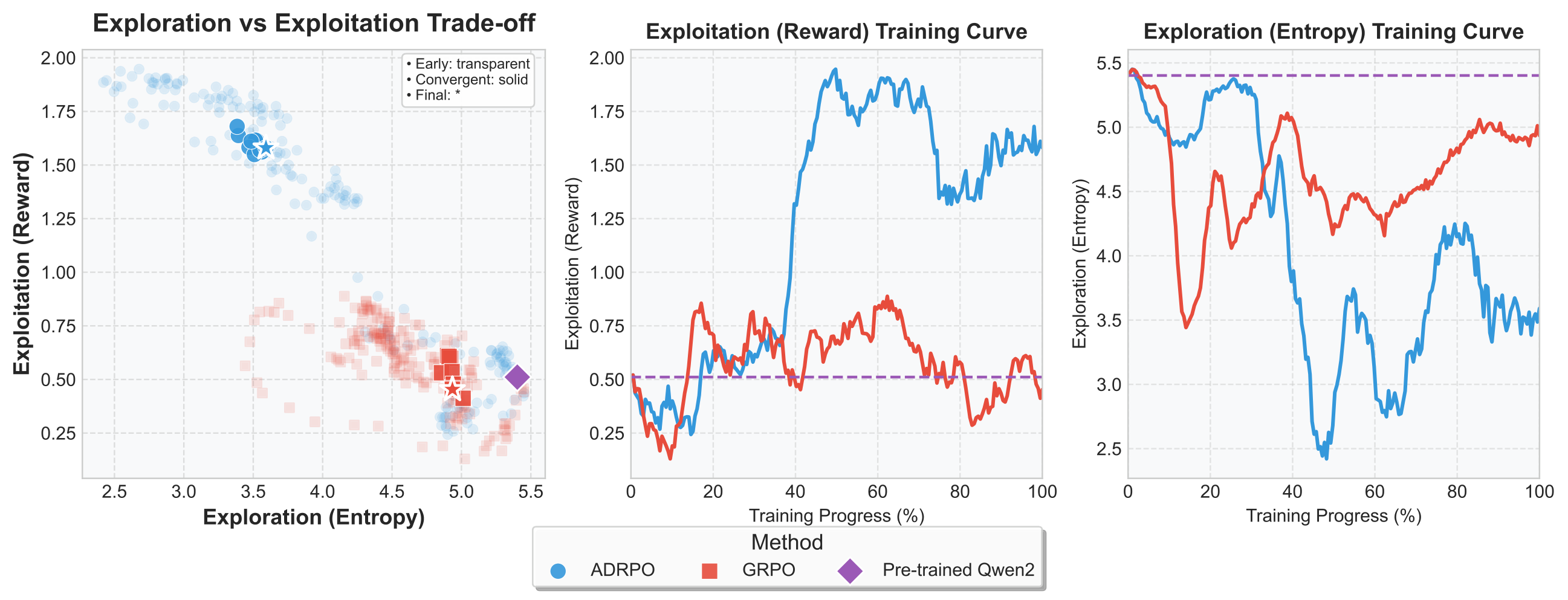

For language models

For LLMs, ADRPO integrates with GRPO by making the KL coefficient advantage-dependent:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{ADRPO-GRPO}}(\theta) = \mathcal{L}_{\text{PG}}(\theta) + (\beta_0 - A_{\text{GRPO}}) \cdot D_{\text{KL}}(\pi_\theta \| \pi_{\text{ref}})\]where \(A_{\text{GRPO}}\) is the group-level advantage from GRPO (reward minus group mean, normalized).

What Emerges in Practice

Smaller models outperform larger ones

With ADRPO, a 2B parameter SD3 model outperforms FLUX.1-Dev (12B) and SANA-1.5 (4.8B) in attribute binding, semantic consistency, and compositional control. The adaptive regularization extracts more from each parameter by allocating exploration budget where it matters most.

Emergent exploration in LLMs

When applied to LLM fine-tuning, ADRPO exhibits an unexpected emergent behavior: the ability to escape local optima.

When the model is stuck in a poor solution (all advantages near zero or negative), the adaptive coefficient \(\beta_0 - A\) increases globally, pulling the model back toward the pre-trained distribution — effectively “resetting” exploration. When it finds a promising direction (high advantages), regularization drops, allowing rapid exploitation. This creates a natural curriculum that no fixed coefficient can replicate.

Cross-domain generality

ADRPO is not limited to one modality or one divergence measure. It has been validated across:

- Flow matching (SD3) with W2 regularization

- Text LLMs (Qwen2, Qwen3) with KL divergence

- Audio reasoning LLMs with GRPO

The same principle — advantage-based adaptive regularization — provides consistent improvement regardless of the underlying architecture.

Summary

The exploration-exploitation dilemma in RLHF is fundamental: no single regularization coefficient is optimal for all samples. ADRPO resolves this by making \(\beta\) a function of advantage:

\[\beta_{\text{eff}} = \beta_0 - A\]One line of math; dramatic practical consequences. For details, see the paper (NeurIPS 2025).

References

[1] Fan et al. “Adaptive Divergence Regularized Policy Optimization for Fine-tuning Generative Models.” NeurIPS 2025. Paper

[2] Fan et al. “Online Reward-Weighted Fine-Tuning of Flow Matching with Wasserstein Regularization.” ICLR 2025. Paper

[3] Shao et al. “DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models.” 2024. (GRPO)

[4] Esser et al. “Scaling Rectified Flow Transformers for High-Resolution Image Synthesis.” ICML 2024. (Stable Diffusion 3)

[5] Rafailov et al. “Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model.” NeurIPS 2023. (DPO)

Cited as:

Fan, Jiajun. "The Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma in RLHF for Generative Models."

jiajunfan.com (2025).